Table of Contents

ToggleIntroduction

When writing a piece of fiction or non-fiction like a memoir, “show, don’t tell examples” is important if you want to truly immerse your reader in your story.

“Show, don’t tell examples” enhances reader engagement by allowing one to see the story through their mind’s eye rather than simply being words on a page.

This article covers various “show, don’t tell” examples that allow your readers to submerge themselves in both the imagination and reality of your making.

Understanding the Concept

To start, “Show, don’t tell” is a principle often used in both fiction and non-fiction writing as a way to give clear visualizations to the readers.

While “telling” has its use, such as when a character needs to state a fact, “showing” is particularly vital to include for limiting the amount of vagueness and cliches your reader experiences.

Moreover, “showing” adds depth to your writing because even if the author can fully picture the story in their head, your reader has no clue of what details you may omit by default.

Benefits of “Show, Don’t Tell Examples”

In popular genres, such as fantasy, “show, don’t tell” is exceptionally important for the sake of world-building, not just for sensory submersion.

For example, “show, don’t tell” helps create emotional connections by putting your reader directly into the shoes of the character’s/narrator’s point of view.

Enhanced descriptive imagery is another aspect of this principle that gives readers fluid expressions of the scene. It can include something as simple as using metaphors your audience can easily interpret or relate to.

Examples of Telling

In comparison, “telling” decreases reader intrigue and makes your story predictable. For example, a narrator may say, “I walked to the park in the hot daytime.”

Anyone could have used this line. It’s no secret that the sun is hot, so using these description types in your story makes it stand out.

Using “showing”: “I walked to the park as the sun reigned above and the heat scorched my skin.” Feel your scenes, don’t just explain them.

Mastering the Art of Showing

Saying the blanket you pulled over your head was “comfy” is not as immersive as saying it “wrapped my head and face in its cotton fibers.”

To create vivid visual imagery, utilizing the senses is key, to both the setting and your character’s/narrator’s actions.

Another important aspect to consider is letting the dialogue do the “showing,” even in the absence of a narrator’s tag. Emphasize tone and behavior through word choices and syntax, rather than through imagery alone.

Painting with Words: Descriptive Scenes

For “show, don’t tell,” keep multiple aspects in mind when setting the scene for your story. This includes where your story is located, what time of day/year it is, and what events are happening around your narrator or characters.

The mood you want to create in your scenery descriptions is greatly impacted by your inclusion of certain colors, landscapes, and objects that provide subtext through symbolism.

One aspect you want to be careful of is not using too many flowery descriptions for an extended portion of your story. Your readers may want your lovely nuanced and artistic descriptions but it’s best not to overwhelm them with pointless elaboration.

Conveying Emotions Effectively

When depicting the emotions of your narrators/characters, you want to “show” what they feel instead of dumbing it down for your readers. This adds to the immersion felt throughout your writing.

Body language and gestures are powerful tools humans use in the absence of words. Scrunching your face when you are angry, or avoiding eye contact when you are ashamed are just some ways our actions depict emotion through “showing.”

An important aspect of this is limiting the use of adverbs. This means avoiding describing emotional actions with words such as “happily” or “charismatically.” Reader immersion occurs when they see how someone acts happy or charismatic, so show them.

Developing Dynamic Characters

Whether it’s an eye roll, the tapping of a foot, or even the way one sits in a chair, all these things paint the picture of the impression your characters give your readers.

· Something I like to do when writing character behaviors/traits is to pretend they are mute. If someone could not speak, how would they communicate? Through specific gestures, expressions, and body language most likely.

· For character growth, “show, don’t tell” is also useful because a character’s inner development is displayed through their actions.

Dialogue as a Tool for Showing

It’s important not to make dialogue too little of a player in your story; otherwise, your readers don’t have room to imagine the scenes themselves through its subtext.

Dialogue allows dynamics between people to be revealed. Their closeness is shown through the context of what they do and don’t say.

Personality traits, such as being sociable or reserved are shown through their engagement, not just how much they converse verbally.

Showcasing Conflict and Tension

Throughout the plot of a story, tension is built both by what your characters directly engage in and witness from the sidelines.

If your character/narrator has disputes with another, making it too obvious could ruin the suspense of your story. You may do this by including subtextual dialogue, or even the mannerisms your character portrays when engaging with their opponent.

The pacing of your story is also crucial to keeping a reader engaged. You may do this by slowing down your characters or quickening them to suit the internal emotions they feel each moment.

Setting the Mood

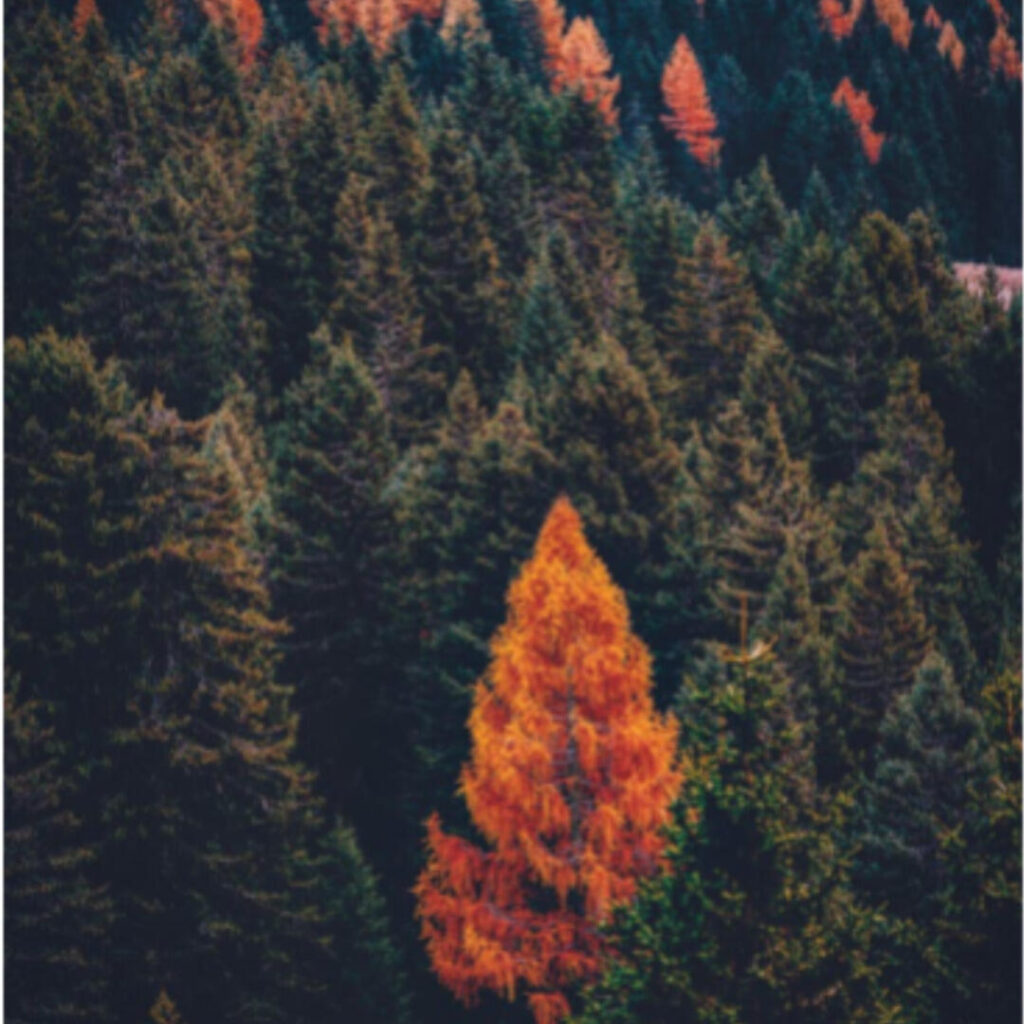

When observing the image above, what do you feel? Maybe it’s the harshness of the rocky stones and cliffs or the somber coldness of the cloudy blue sky.

To set the tone of your story, it is important to include sensory language that depicts aspects such as sight, sound, smell, touch, and taste.

Additionally, you want to keep the emotional grounding points of your story in mind with these descriptions. Pay close attention to specific textures, smells, sounds, etc., that vary in relatability to what your reader can realistically comprehend.

Show, Don’t Tell Examples in Different Genres

Fiction is not the only type of writing that benefits from “show, don’t tell examples.” Any genre or style of writing can garner reader interest, regardless of whether it’s real or imaginary.

Each genre is different regarding how you should “show” a story to your readers. In fiction, for instance, “showing” provides a dreamlike immersion for a made-up story. In comparison, non-fiction uses “showing” to connect readers with real-world experiences and people who exist but whom they may have not yet encountered.

An example of “showing” in horror fiction could be describing the texture of blood splashing across one’s face. For fantasy, it may be the description of how loud the roars of a dragon are. Whereas romance may entail descriptions of a love interest’s physical appearance or kind gestures they make to another.

Editing for “Show, Don’t Tell”

A way to identify “telling” is to pay close attention to the vague use of adverbs. This also includes spotting one-dimensional statements made by your characters/narrators which add no subtext to a scene.

A weak passage, for instance, may be riddled with adverbs or statements like, “I didn’t like the food.” Instead, describe the expressions/gestures by said character, or the five senses experienced when eating said meal.

In the writing workshops I’ve participated in, grounding my peers in a clear setting took practice, and still does. Don’t be afraid to seek feedback on specific aspects of your story like imagery and setting clarity. You’ll be surprised to discover how much you have yet to show your audience!

Exercises to Improve Showing Skills

To strengthen your “showing” skills, jot down any observations you make about something. Something I deliberately practice when walking, sitting, talking, etc., is to look up, down, and all around! Focus on the details in your environment that you don’t always acknowledge or put value in.

A book that does “showing” well is The Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde. The author will use imagery to establish mood and symbolism that connect the reader to the story’s broader themes and experiences of its characters. This is shown in the description, “…The glow of hot autumn afternoons on hillside vineyards, was ready to be set free and to disperse the fogs of London” (Stevenson 32).

Common Pitfalls to Avoid

Extraneous details in a story can bog down its pacing, and your readers’ ability to comprehend the text. Make sure most, if not every, detail included serves a purpose.

Likewise, “showing” is not always necessary in your writing either. If certain details/descriptions do not drastically change the trajectory of your story’s purpose, feel free to omit the fluff.

Show, Don’t Tell in Non-Fiction

The notion of “clarity” is key in writing articles and essays. Both fiction and non-fiction works seek to inform readers, even if they vary in their topics.

To enhance this clarity and engagement in non-fiction, assume your readers are unaware of the setting or subject matter.

Examples of effective showing in real-world writing:

Using Metaphors and Similes

Figurative language is another technique often used for “showing.” Comparing certain concepts, entities, or scenarios to each other will give clarity and subtext for the readers to dissect.

It’s important to keep your story’s purpose in mind when using metaphors and similes. Using “she danced like raindrops” in a story about deadly hurricanes could be insensitive to readers due to this simile’s lighthearted tone.

Avoiding cliches is a big one in this regard. A quick way to bore your reader is to use comparative language that has been told a thousand times before. Be creative and make the language your own. Instead of “light as a feather,” try phrases like, “light as a dried-up sponge,” or whatever suits your stories’ tones/themes best.

Show, Don’t Tell Examples in Action Sequences

If a character is in a fistfight, how quick are their movements? Which direction are they dodging in? What do the blows feel like? Fully encapsulate thrilling sequences with as much imagery and realistic movements as possible to help keep readers engaged.

However, remember not to sideline character development for a quick buzz of action. Character depth is part of plenty of readers’ entertainment, not just because of the story’s flashy choreography.

Final Thoughts

Overall, “show, don’t tell” is important to apply to your writing because a reader’s natural senses are the strongest tools you have to captivate them. An audience’s comprehension of your story mainly revolves around the “mind castle” through which you emotionally transpose them.

This is done through your writing’s inclusion of a setting’s imagery, character subtext (dialogue and behavior), and establishing mood and dynamism through your creative use of language.

Regardless of whether you write for romance, thrillers, fantasy, fiction, non-fiction, etc., you are not alone in your journey of crafting an immersive world for your readers. Plenty of writers have struggled with “show, don’t tell,” but your weaknesses in utilizing it effectively are not your future promise.

·“Show, don’t tell” was one of the things I struggled most with when I first started writing, as it was hard to translate the imagery in my mind to words on a page. So, don’t think you are doomed to an endless uphill battle. With continued practice, feedback from others, and curiosity toward surpassing your writing’s potential shortcomings, I know that you and your future readers will gladly reap the fruit of your hard-earned growth.

Keep striving, writers!

Until next time.

Are you an aspiring writer who is Tarafied to Publish? Or do you have a book inside of you but don’t know where to begin the publishing process? Book a Call, HERE.

Frequently Asked Questions

If you have a narrator describing a fearful encounter in the ocean, you might say, “I had gone into the grayish blue waves at waist deep, but a slick, thick mass brushed against my leg as I reached the underwater bunker.”

The description mentioned in the previous answer clarifies why the narrator is afraid. In the above answer, the narrator cannot see what is lurking beneath them. Even if your reader has never encountered a shark, this scene conveys the common “fear of the unknown” many people have, making it quite effective.

A way to exhibit anger in a story could be, “His jaw and fingers clenched as his nails dug deeper into the crevices of his palms.” Next time you or someone else gets angry, take notes. What do you physically see in that moment?

Related Articles

Author’s Purpose: Key Insights Into Writing Intentions

Author